My last blog post, I announced that I was awarded the Marie Curie Individual Fellowship from the Horizon 2020 fund from the European Commission. And I promised to give details about the actual project. Et voila!

Antimicrobial resistance

You’ve probably heard of antibiotic resistance? It’s when the bacteria that’s caused an infection in someone is resistant to the treatment used to kill it off. It’s scary stuff. It’s not just bacteria that develops resistance to treatment. Viruses and parasites and fungi do too. The umbrella term is antimicrobial resistance (AMR). And AMR is a big deal! When a treatment stops working, morbidity and mortality from the disease goes up. New drugs need to be developed, which takes a lot of time and money. And even if new drugs were as easy to develop as a new tea flavour, to be effective to the resistant strain, the new drugs are often more toxic, leading to harsher side effects. And often the new drugs are more expensive, which can make them inaccessible to many patients. The consequence of AMR are so far reaching, that addressing AMR will help 6 out of 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals set by WHO.

What makes a microbe develop resistance? Nature. Consider a sick person, and the offending microbe is multiplying like crazy within this person. Mutations of the microbe occur all the time, and VERY occasionally some of these mutations will lead to a resistant strain. When the settings favour this resistant strain, such as when the sick person gets treatment which kills off all other strains, the resistant strain has an evolutionary advantage. The sick person remains sick. And the infectious disease continues to spread. The resistant strain of it. Dun dun dunnnn…

Drug resistance in low to middle income countries.

To prevent drug resistance, treatment needs to be effective and the full prescribed course of treatment needs to be completed. However, this can be difficult to monitor, especially in low to middle income countries where health care access may be limited. For example, someone may feel better after a few days of treatment, and save their medicine for a family member who has the same symptoms. Or perhaps treatment is cheaper from a family friend with boxes of cheap (presumably counterfeit) drugs. These factors are known to promote drug resistance occurring and spreading.

Monitoring drug resistance spreading

Consider malaria, a parasitic infection. The latest treatment used to combat malaria is artemisinin. Like all antimalarials that came before artemisinin, drug resistance to this treatment starts in South East Asia. When drug resistance malaria infections occur in Africa, where malaria prevalence is very high, the tragedy rapidly escalates. Consequently, drug resistance is monitored globally. The map below is from many molecular marker studies, beautifully collated together by WorldWide AntiMalarial Network (WWARN). These studies take samples from infected people and identify whether the malaria parasite within them has mutations which are associated with resistance to treatment.

My project – the science bit

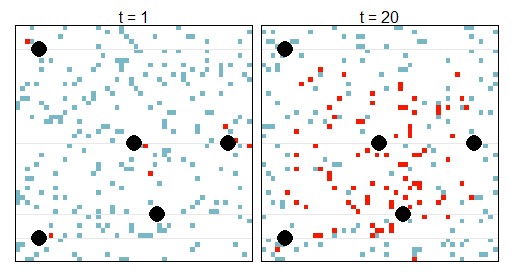

To demonstrate my project, consider a toy example in Square Land over 20 years. Within Square Land you have sampled infected people, at different locations and times, and identified whether they carry a resistant strain or not (like the WWARN data above). In addition, suppose you know the location of five treatment access points, such as health care centres or hospitals. The first and last year look like this.

The black circles are the treatment access points. A red square means that at that location and time, there is at least one infected person carrying a resistant strain (yi = 1). A blue square means that at that location and time, there were no sampled people carrying a resistant strain (yi = 0). In total there are N data points (y1, y2, … , yi, … , yN), collected over the 20 years. The ‘true’ number of people carrying a resistant strain will be greater, this is only the collected data. In other words, each data point yi has a probability pi of being a 0 or 1, where pi depends on the true density of people infected with a resistant infection at that particular location and year, ui, and a probability of being sampled. The sampling probability depends on demographics about the person, such as their age.

The true number of people with a resistant infection at a particular location and year, ui, is unknown. However, we assume some basic knowledge about the underlying processes which determine this truth. That is, we assume that the true number of people with a resistant infection at a particular location and year, ui, depends on (1) the number of people with resistant infections in the neighbouring regions, and (2) the number of people with resistant infections at the particular location during the previous year. Both of these components depend on the prevalence of the disease in general. Processes (1) and (2) are standard assumptions regarding species spread – dispersal and growth. I added a third process which is specific to drug resistant infections: (3) new introductions of the resistant strain – which is an underlying spatial component that states there is more chance of having a resistant strain when close to a ‘hot spot’, where each hot spot has a different magnitude of resistant infections that it contributes into the population. For simplicity, in this example, I previously stated that all these hot spots are treatment access points, however one or more of them could be a transport hub such as train station or airport. Also, for simplicity, I’ve assumed that we know the location of the hot spots (however this isn’t a requirement of the method).

Using Monte Carlo Markov Chain with uninformative priors (translation: using powerful statistical tools combined with computing power and assuming no previous knowledge – which could introduce biases), we can identify which hot spot is contributing more resistance to the population and target strategy accordingly. In this example, we identified that the top left hot spot contributes the most resistant infections into the population. Therefore, if this hot spot was a health care centre, it would be worth investigating the quality of the drugs administered here and/or the adherence of the patients. If this hot spot was a transport hub, it would inform us that drug resistance is entering the population from outside.

Some of you may be disappointed that I haven’t presented the beautiful equations that describe this whole process. If you want all the juicy details, feel free to reach out or peruse a recent presentation I gave at the Research Center for Statistics at the University of Geneva, available here.

My project – the me bit

I’ve had a varied research background (see previous blog post: From electricity to malaria). This meant that from my PhD, I’m familiar with partial differential equations (used here to model the mechanisms of the true number of people with a resistant infection at a particular location and year). From working with ecologists, I’m familiar with Bayesian hierarchical models being used to model animal movement, which formally accounts for uncertainty in the data . And from working with epidemiologists, I’m familiar with drug resistant malaria. Put it all together…. and what do you get!? I believe the first time that this type of model is applied to understand the spatio-temporal mechanics of AMR in a population.

This blog post provides a comprehensive overview of antimicrobial resistance.

Thanks for taking the time to read my thoughts 🙂 And always good to get external approval about my interpretation and communication of the science!!