Women! Huuzzaarrr!!!

This year, I did something that I wouldn’t have foreseen myself doing. And that’s quite a thrill!

Let’s start aaall the way back at the beginning…

My Mum and older (and only) sister are dyslexic to quite a high level. As the only females in my life for a long time, I assumed, on some level, that women don’t know “school” things. I don’t remember thinking it directly. But I do remember once asking my grandma how to spell something and then saying, “Oh wait, you won’t know.”. I was surprised when she said that she did, and told me how to spell it. And I don’t think I’ve ever directly assumed intellect again based on gender.

I think part of this is going to an all girls school. There are no conversations comparing boys to girls abilities when it’s all girls!

When I went to college, I never questioned being among mostly boys in my maths class. My two siblings closest to my age are my brothers – obviously a random occurrence of events. So to be in a class of mostly boys was something that perhaps I unconsciously put down to randomness (a theory which a moment of conscious thought, and some simple probability would have squelched).

At university, for my degree, it was 50/50. Yet I felt quite apart from the girls. My closest class mate was a boy. Usually him and I would mess about at the back, giving each other stupid dares. Despite this tomfoolery, I aced my undergrad, and graduated with the highest grade that year. (I miss the days when you can have your ability quantified like this – I’ve struggled to feel academically-capable ever since such categorical ranking!)

I ate a packet in one go: I lost a bet about what colour jumper our lecturer would wear.

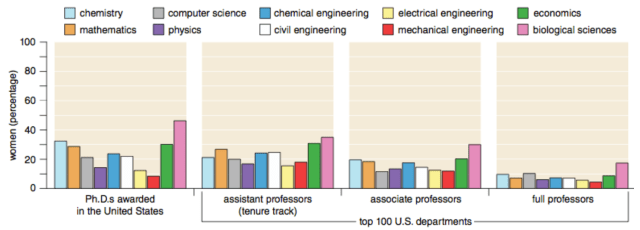

Again, my masters and PhD was 50/50. Which I later found out was intentional. I was so oblivious to maths and gender issues that when my PhD supervisor suggested I go to the “Women in Maths” conference, I asked, “What’s the point in that?”. I didn’t want to go to a conference that targeted my gender and not my research topic. He pointed out the leaky pipeline. I didn’t quite get it. And it sounded like a general career thing bigger than “Women in Maths”. I thought, “But that’s how it is in all sectors”. Essentially, “But that’s just how it is!” Nonetheless, a seed was planted. I went to the conference.

The leaky pipeline in STEM subjects, 2007. Ceci and Williams (2012)

Fast forward to my postdoc in an ecology department where I had more female colleagues than I’d ever had up to that point! And as a lab, they talked a lot about women in science. At the time it was paradoxical to me, that I would have more women around me, yet more discussion about the lack of women.

That seed planted a few years before was being nurtured and growing. Although I was still, on some level, struggling to see what the fuss was about.

Then a PhD student in my office said that at school she was told that she was, “good at maths for a girl”. I feel blessed, and also ignorant, that this mentality was new to me. And the ludicrousness of it still stays with me.

After this position I went back to a maths department. This time I noticed what I hadn’t noticed before. The culture is different when you’re in the minority. To make it worse, we collaborated with the electricity industry. Whereas in maths, there would be 7-10 men for every women, in electricity, it was 15 to 18. And was the electricity industry having a conversation?!!? Of course not! All-Male panels were a given!

The theme tune in my head when I go to maths, stats and electricity conferences. Skepta – We need some more girls in here! We need some more girls in here!

With my new awareness, I noticed I was being talked over. I would be responsible for cleaning and prepping the data (which, I learned, is not enough to be included as an author). Tasks set to us from our electricity partners were handed to my equal, male-counterpart for him to delegate to me. I would receive the odd comment that made me acutely aware of my gender. Perhaps, without being involved with the conversations previously, I wouldn’t have noticed these behaviours, but now I did, I couldn’t not see them!

I have to be clear, the Mathematics Institute is fantastic. And I recommend anyone, male or female, to get involved if they can. There’s lots of reasons why it’s truly fantastic, the members of the institute being a significant one. And there is a strong awareness of the gender imbalance, and efforts constantly being made to balance it.

For me, and my demeanor at the time, I became less and less enthused with the work. When you try and talk 15 times in a single meeting (I had a tally), you simply stop trying. My confidence was shot. I constantly felt inadequate and that I couldn’t do the work, so I tried less hard. So I really did become less capable. It became a chicken / egg situation.

However, again, this is how I felt. I’m certain some men in a maths department struggle in the same way. It’s essentially a question of confidence and assertiveness, which may be lacking for a plethora of reasons, from language to personality to gender.

As I say, there are real efforts being made to address gender imbalance. There were regular “Women in Science” events and workshops, which I attended with gusto (unlike my PhD self!). We were instructed to not apologise or thank without reason. Don’t say, “May I say..” before saying your point – just say it! Overall, the advice was to not seek permission to be there: own your space, position and intellect.

Armed with this advice I would have two iterations of each email I wrote. One to write what I want, and another to edit it to be more direct. This simple act was surprisingly stressful! I didn’t enjoy sending emails that, to me, felt rude. My personal motto is that it’s nice to be nice! So I dropped the advice to be direct, and in fact, as an act of rebellion, I now sign off all my emails with, “Thanks” instead of “Regards”.

My life motto! And I do like a Nice biscuit 🙂

Nonetheless, some of the advice I try to keep. Namely, don’t question your intellect on your subject. I couldn’t really quantify what that looked like until a male colleague and me sent a paper to review. Sitting in the same office, we both read the rejection email at the same time. My heart sunk as I read it. I thought, “We did it all wrong!”. My mind starts spiralling, “Why I’m in research at all?”. But my mind doesn’t spiral far because the first thing that came out my colleagues mouth? “This reviewer doesn’t get it at all!”.

And so now…

Scientists often leave their field because of a vibe that their well-intentioned colleagues were unconsciously putting out. And perhaps the scientist in question isn’t even aware that it’s getting them down. They put their feelings of dissatisfaction down to other factors. But perhaps those factors would seem manageable if they feel valued and included.

I think we need to discuss our work culture, and invite others who may feel that they’re not entitled to share their opinion, to share their opinion. Learn from others who have worked elsewhere. What’s their impression of the work environment? Take nothing for granted as “This is the way”. Instead, strive for a work environment that can nurture individual creativity and intellect. And this isn’t on HR. We can, and should, figure out ways we can support each other. We all want to love our job, and work with others who also love their job! And perhaps this love-fest will harvest better science!

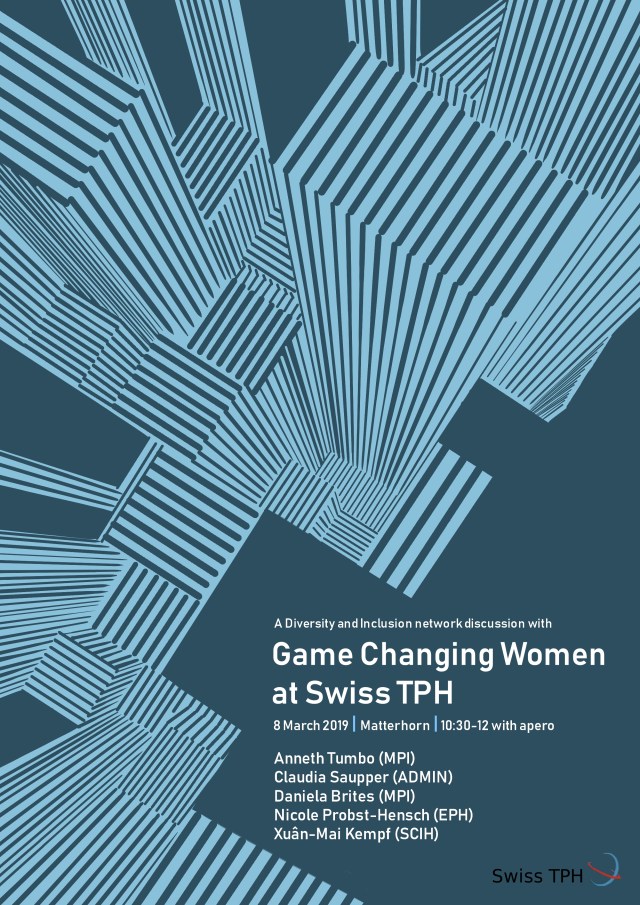

With that in mind, some sterling colleagues of mine organised a “Game changing women at Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute” event. We had five colleagues honestly and bravely answer some very personal questions. We were astounded at the turn out. There is clearly a desire to help each other find a nuanced path that feels true for each of us. And let’s respect each others outlook, especially when they’re different to ours. What experiences have others had that led to such a difference? Dialogue dialogue dialogue. But maybe that’s just me being a nattering old hen…. Sorry and thank you 😉

Questions posed to panel members here. What would your answers be? Poster designed by Mark Peacock.

Nice article, From World Eye Watch